Revisiting Critical Design Decisions

1. Introduction

Our group has spent approximately the last three weeks attempting to install a Linux distribution and Robot Operating System (commonly known as ROS) on a microcomputer in the hopes of running a Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) algorithm to do navigation with the Neato Lidar.

2. Working with ROS

We were initially advised by our professor to use ROS and Ubuntu on the Beaglebone Black to tackle our navigation problem. The main rationale for the platform was that the graduate team in mLab was using a similar setup so we wanted our vehicles to be compatible in the event that they were to communication or co-operate. Eventually, for reasons detailed below, we decided to switch from the Beaglebone Black (BBB) to the Raspberry Pi 2. We attempted each of the following platforms in chronological order:

Ubuntu on the Beaglebone Black

We started with the trying to install Ubuntu 14.04 on the Beaglebone Black since that is was the mLab team was using. After a successful installation of Ubuntu and ROS, we started to install BlackLib. After debugging the Makefile, we successfully compiled the library and discovered runtime errors. Finally, we determined the errors resulted from the filesystem not containing the standard BBB device tree (usually under /sys/dev). This was a critical issue since it prevented us from accessing any of the BBB’s GPIO pins and would require very low level manipulation of the operating system to fix. Furthermore, we were unable to get connectivity via Ethernet and instead relied on RNDIS, a protocol for virtual Ethernet over USB, which would not be sufficient for a robot.

Debian on the Beaglebone Black

We attempted to install Debian next on the BBB since it has more support from the Beaglebone community. However, we were unable to find any evidence of people who have successfully installed ROS on the BBB running Debian.

Angstrom on the Beaglebone Black

Finally, we found a port of ROS, Beagle-Ros for the BBB on Angstrom, a Linux distribution specialized for embedded systems. The installation guide for Beagle-Ros urged us to get the latest image of Angstrom available. However, the most recent compiled image for the BBB is from September 2013 and our then-mentor Steven told us the build process to create an image from source is complicated and can take many hours. So, we tried to proceed with the 2013 image but ran into a few critical issues.

First, we found that the OPKG software repositories supported by this version of Angstrom only contains up to git-scm 1.7.7, which is ~4 years old. In fact, this version of is so old that it’s no longer supported by GitHub, and thus we were unable to download the Beagle-Ros project. An attempt to build git from source turned out to be non-trivial, as Angstrom lacks some basic build tools. After reading more into Beagle-Ros, I also discovered it did not support direction compilation of ROS catkin packages. Rather, packages needed to be stored on an Ubuntu dev environment and then cross-compiled to Angstrom.

Angstrom also presented a couple of more minor issues. In addition to build issues, we were unable to get Angstrom to either flash onto the BBB’s eMMC or to get the BBB to boot from the microSD card without holding the boot select button. Furthermore, we had issues configuring the RNDIS interface but were able to get it to work by removing the network manager and creating a manual configuration. In the end, Angstrom presented too many issues and we opted to abandon it.

Debian on the Raspberry Pi

After three failed attempt of getting ROS working on Beaglebone and exhausting our options, we opted to change microcomputers. In summary, we found the Beaglebone to be a poorly supported platform with a lack of recent documentation and community involvement. We chose instead to move to the Raspberry Pi 2, which is cheaper, more powerful, more popular, brand new, and surrounded by a prolific community of hobbyists and researchers. First, we installed Raspian, a Debian port, which is the most popular operating system for the Raspberry Pi. We found a community-authored tutorial for installing ROS on the official ROS wiki.

We worked successfully through the installation until we attempted to install non-core packages using apt-get (Section 3.2 in the tutorial). At this step, we ran into a dependency error for “python:any (>= 2.7.1-0ubuntu2)” which caused the package installation to fail, despite our having Python 2.7.3. After some research, we discovered the issue was that the version of apt-get for Ubuntu is newer than the version of apt-get for Debian and supports the “:any” qualifier. Since Ubuntu is the official distribution of ROS, the dependencies were specified assuming an Ubuntu system. Based on community posts, it seems as if this issue only came up in the last year or so, and we found suggested solutions online to no avail. After exhausting our options, we decided to try to run Ubuntu on the RasPi 2.

Snappy Ubuntu Core on the Raspberry Pi

We elected to move to an Ubuntu image since it is an extremely popular distribution and the official supported operating system for ROS. The Ubuntu image officially supported for the Pi is called Snappy Ubuntu Core. It is designed for Internet of Things devices and lacks many of Ubuntu’s core features (like apt-get) in favor of more specialized alternatives. After determining this version of Ubuntu would be incompatible with ROS, we searched for an alternative.

Ubuntu on the Raspberry Pi

After some searching, we discovered a full-featured version of Ubuntu that runs solely on the Raspberry Pi 2. Furthermore, this distribution has a fair amount of support from the Ubuntu and RasPi community and includes drivers and a device tree for the board’s GPIOs. We were able to install ROS using the official installation guide without any major problems. We were also able to install and use WiringPi to generate PWM signals and to control GPIOs.

Decision to Abandon ROS

With ROS installed and working, we were ready to start implementing the navigation slack that would allow us to leverage ROS’s slam algorithms, which is our original reason for using ROS. We worked through ROS tutorials to get a feel for how the framework works, but the navigation stack is complicated to implement. We consulted the research team in mLab to get advice on where to start. After seeing the velocity of their progress with the same framework and algorithms, we determined that implementing SLAM with ROS is infeasible given the timeline of the ESE 350 final project.

3. Revisiting Navigation

After deciding to abandon ROS, we revisited our options for a navigation system. Our requirements are absolute positioning and relatively fine granularity (down to ~1cm). The first idea was to encode information via a track system using either optics or magnetic fields. The optical approach would consist of creating a printed track with position information encoded in the track line, much like a 2D barcode. The car would drive over the encoded information and read the data using a phototransistor and information from the motor encoders. Then, it would combine relative information from dead-reckoning (using motor encoder information) with the rough absolute position based upon the read-in pattern to determine its absolute location. The magnetic approach would consist of placing magnets below the track and using a Hall Effect sensor to detect the car passing over the magnets. Both setups would use line-following to stay on the track. Both approaches could be taken a step further by activating only one point at a time using either LEDs or electromagnets. By cycling through each point quickly (at about 10Hz) and using precise timing, we could determine which electromagnet or LED the car was passing over.

We created a list of pros and cons for each of the navigation ideas, trading off between cost, complexity, and accuracy. Because of issues with timing and uncertainty of the methods, we decided in the end to stay with the LIDAR. However, rather than using it for SLAM, we want to use it to track the locations of four walls surrounding our track. As long as the robots know their precise starting position and orientation, we can use image processing to determine the absolute position and orientation of each based solely on LIDAR data.

4. Moving Forward

(No pun intended)

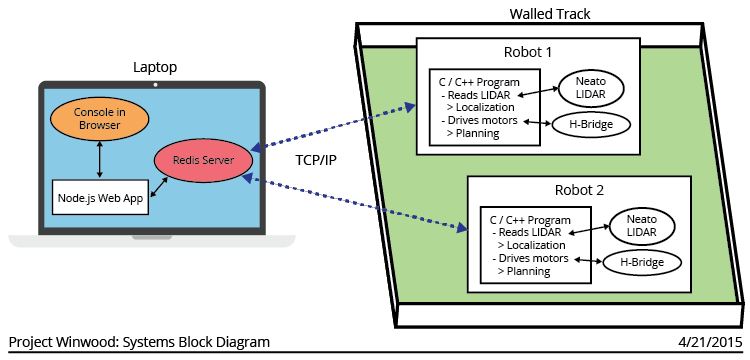

With a more promising plan for a navigation system in mind, we revisited the high level design of our control system for the robot. A block diagram of this design is displayed below:

We will use a Redis server running on a laptop to pass information between robots and between robots and the user console. We will write code for each robot in C/C++. The code will consist of a Redis client, a LIDAR Reader, a localization algorithm, and a planner than decides where the robot goes. On the laptop, there will be a web-based user console running in a Node.js web app that will allow the user to enter commands, visualize the robot’s data processing, and get logging and feedback information.

Baseline for Friday, April 24th

The baseline assignment will be to get one robot to be able to use the LIDAR to determine its position on the track and to navigate when given commands from the user console.

Reach Goal for Friday, May 1st

The reach goal will be to have multiple robots communicate via the centralized server and to negotiate in traffic scenarios.

5. Lessons Learned

- Opt to use technologies that are well supported in the community. The timeline of this project does not allow new technologies to be explored since there is the potential to spend tens of man hours exploring systems that are merely small components of the overall project.

- Avoid complicated frameworks like ROS at all costs, since there is a steep learning curve and most support is either too broad or overly specific to one scenario.

- Always keep a realistic timeline in mind leading towards an end goal. As estimates change, so should the goal and methods to match the resources available.